Yesterday, August 11, the Ringgit breached RM4.00 for a dollar.

When I logged in to my Facebook and Twitter accounts, 9 out of 10 posts that appeared on my timeline were slamming the Government on the Ringgit.

To sum them up, youths who dominate social media today were posting comments as though tomorrow spells the end for Malaysia.

And in just the past month, I saw how Malaysians transform from being constitutional experts, to aviation analysts and now economics.

Some even went as far as pushing the blame on Umno and Najib. There’s this group called Suara Rakyat who likes to say “other countries are doing better because Umno is not there in their country”.

Of course, when you have a narrow, myopic view, you will tend to miss out the fact that over the 5 year period

• Russian Roubles lost 114per cent against USD

• Indonesian Rupiah lost 51per cent against USD

• Indian Rupees lost 38per cent against USD

• Norwegian Krone lost 37per cent against USD

• Australian Dollars lost 24per cent against USD

• Euro lost 20per cent against USD

• Thai Baht lost 10per cent against USD

Do I need to go on?

One of the contributing factors faced by these countries is the drop in oil prices. Crude oil was trading at US$70-80/bbl few years ago and today it has fallen below US$ 50 per bbl.

China again devalues their currency a second day. A 1.6% drop on top of the 2% drop yesterday. Regional stock markets and Asian currencies will all experience more drops again.

Also, US is not our only trading partner and the performance of our Ringgit is not measured against US dollars alone. When we look at the Ringgit,

• we strengthened against Canadian Dollars (2per cent)

• we strengthened against Indian Rupees (10 per cent)

• we strengthened against Japanese Yen (14 per cent)

• we strengthened against Indonesian Rupiah (18 per cent)

I don’t need to name more currencies, do I?

Do you know that the value of our trade with India, Japan and Indonesia is close to 20per cent? Understandably, we are quick to feed on negative news and quick to comment like an expert on our Facebook and Twitter. That’s how things work these days.

Of course, none of you made reference to 1998.

No one remembered the time when the Ringgit crashed to as low as RM4.725 for a dollar on 7 January 1998 (BNM selling rate, over the counter was more than RM4.80).

All of you, who were quick to comment about the state of our economy on your Facebook, were still in school.

So none of you knew, none of you remembered, none of you experienced what happened in 1998 when Anwar Ibrahim was Finance Minister.

Back then

a) People were losing jobs or had difficulty in getting jobs

b) Households were squeezed

b) average lending rate was 12.16 per cent

c) Inflation was close to 3 per cent without subsidy removals.

If any of you doubt the 2-3 per cent inflation numbers today and felt it is way higher, apply the same thought to 1998-1999. And yes, average lending rate was over 12 per cent. Those were the days.

You may say it is history and you may continue to slam the Prime Minister, the Central Bank and the Government for today’s numbers.

But the next time before you give you get upset and share your anger on Facebook or Twitter, ask yourself whether or not the Ringgit — Dollar exchange rate affects you, and how.

1. Do you shop online from US websites?

2. Are you planning to fly over to US for a holiday?

3. Are you a Malaysian studying in the US?

4. Do you import goods to be resold in Malaysia?

5. Do you buy necessities and food from the US to use here?

6. Do you at all use the US dollar in your daily life?

Because my dear, only if you answer yes to the above, you are affected. Otherwise, what are you shouting and so worried about? Your salary is still denominated in Ringgit and you don’t buy necessities with US dollars.

Sure, no one can deny that it has some impact to some segments especially imports and our plans to travel to US, UK etc. I am also of the opinion that there are many things Najib can do (which he isn’t at all now) and I will share more soon.

And guys, the international ratings agencies — Fitch, Moody’s and S&P — have all maintained Malaysia’s outlook as stable.

There are no economists out there who are saying that Malaysia’s economy will collapse, only politicians are saying this.

The MYR has suffered a 20pt drop against the USD, but less than half that against the full basket our trade partners currencies. The impact on prices of imports should therefore be correspondingly less. By the same token, there won’t be a sudden boom in exports due to a “weaker” Ringgit, because the Ringgit hasn’t really dropped that much.

Even more important is the second factor – the drop in commodity prices (IMF All Commodity Index; 2005=100):

Aggregate commodity prices have dropped by a full third in the second half of 2014; a select few, like crude oil and iron ore, have dropped even further. What this means is that energy and raw material input prices for finished goods have dropped substantially. International producers can mostly afford to maintain local pricing for goods, because their profit margins have increased enough to offset the lower revenue (in USD terms). A few have taken advantage of the changes in terms of trade to try and have it both ways (higher retail prices + lower input costs), but most are content to maintain their margins.

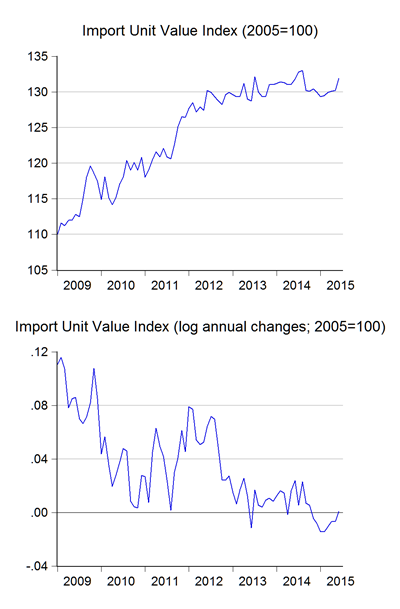

Forget imported inflation – we’ve been importing deflation since last year (index numbers and log annual changes; 2005=100):

More formally, I’ve tested the impact of changes in USDMYR on import prices, using a data sample from the start of the float of the Ringgit in July 2005 to the present. There is a very weak correlation, but once you account for serial correlation (from import price persistence), the result is a big fat zero. Movements in the exchange rate are NOT driving changes in imported inflation, much less inflation as a whole.

Moving on to the role of international reserves. I’m continually bemused by the tendency of nearly everyone (local and abroad) to analyse the situation as if we still live in a Bretton Woods world. So let me make it clear – in a floating exchange rate regime, international reserves don’t matter. The choice of whether to utilise international reserves to support the currency is solely a matter of central bank discretion.

In the present circumstances, it’s not even clear why BNM should in fact intervene. You can make the argument that the Ringgit is fundamentally undervalued, and the FX market has overshot; but I have no idea why this is considered “bad”. If you want to live in a world of free capital flows, FX volatility is the price you pay.

The vast majority of the population will not be affected – the ones who are, are mostly in the upper tier of the income distribution and can presumably take their shopping elsewhere (I’m buying stuff off EBay Germany these days). Concerns over imported “inflation” hitting the man on the street (or businesses for that matter) are overdone, as I’ve demonstrated above. Multinationals who dominate Malaysia’s manufacturing sector don’t care – both their outputs and inputs are denominated in USD, and the decline in the exchange rate just improves their domestic profit margins. The capital markets are obviously affected by capital outflows, but then Malaysia’s equity and bond markets were pricey anyway, and amazingly still are relative to the rest of the region. All the doom and gloom on the markets appears to have glossed over the fact that Malaysian market valuations are just coming down to the regional average.

Again, to put all this into context, Malaysia’s latest numbers puts reserve cover at 7.6 months retained imports, and 1.1 times short term external debt, versus the international benchmark of 3 months and 1 times. Malaysia is at about par for the rest of the region, apart from outliers like Singapore and Japan.

Australia and France on the other hand, have just two months import cover, while the US, Canada and Germany keep just one month. You might argue that since these are advanced economies, there’s little concern over their international reserves. I would argue that that viewpoint is totally bogus. Debt defaults and currency crises were just as common in advanced economies under the Bretton Woods system. The lesson here is more about commitment to floating rather than the level of reserves. One can’t help but see the double standards involved here.

Also missing in the commentary is the cost of accumulating and maintaining international reserves. Since buying reserves is inflationary and thus needs to be sterilised, and because the interest rate differential is typically positive between domestic and reserve currency rates, international reserves typically involve a net loss to the central bank and the country (unless you’re willing to take some risks). {The opposite is also true – utilising reserves to support the currency is deflationary, and thus undermines the economy through tighter monetary conditions. I really wonder why people think “stabilising” the exchange rate is such a good idea].

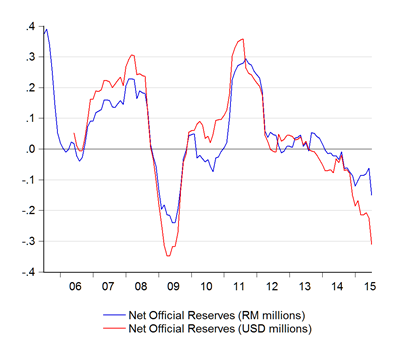

Another big issue is the habit of quoting reserves in USD terms. In a world where the USD is appreciating against nearly all other currencies, movements in international reserves are artificially exacerbated, as nobody keeps all their international reserves in a single currency. This habit can cause some embarrassment for the analysts involved, as in this smackdown by Singapore’s MAS earlier this year. BNM really ought to issue a similar statement (log annual changes; 2005-2015):

Note that reserves in USD terms is far more volatile than in MYR terms. People will of course look at the steep drop in reserves since 2014. To which my response would be: so what? I repeat: we’re not living in a Bretton Woods world of fixed exchange rates. BNM can, and in my view should, stop intervening, until and unless the banking system itself is running short of USD.

Speaking of which (RM millions; 2005-2015):

Looks pretty healthy to me. The banking system were under greater stress after the the “taper tantrum” in 2013.

All in all, this alarmism betrays a lack of general economic knowledge in Malaysia, even among people who should know better. Or maybe I’m being too harsh – it’s really a lack of knowledge of international macro and monetary economics.

I recently met an Australian trade delegation, who were smugly proud the Aussie dollar has crashed. The only reason why the Ringgit is the worst performing currency in Asia, is because nobody considers Australia as being Asian (which must frustrate the Aussie government no end).

The Bank of Canada, the Reserve Bank of Australia, and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, have all aggressively cut interest rates and talked down their own currencies – it’s the right thing to do in the face of a commodity price crash. BNM on the other hand has to walk and talk softly, softly, because Malaysians seem to think the Ringgit ought to defy economic laws.

Adapted from JUST READ and Economics Malaysia Blogs